Editorial

The theme of this edition of 'Don Bosco Today' is vocation. In April we were delighted to welcome to our province Fr Pascual Chávez, our major superior from Rome, the ninth successor of Don Bosco. He only stayed a few days, but he made a great impression on everyone he met. At meetings, organised at Bolton and Chertsey, he spoke to us about his own vocation and the meaning of vocation today. We all have a vocation, we are all called to spread the good news of the gospel. In this edition I have tried to give examples of the way God continues to call people today, from teenagers to grandparents. Many of you will have heard of Sean Devereux, who worked so generously for disadvantaged children in Liberia and Somalia, and was so tragically killed in Somalia in 1993. I have included an article on Sean, because he is an example of the generosity we see in so many young people today. We are thinking of publishing a book on his life which may be of use in schools. I would welcome any insights into his character from those of you who knew Sean.I would like to thank those of you who sent us donations for our mission work. Your generosity amounted to over £7000. This has been passed on to Fr Joe Brown, our Mission Director, who will use it to help the street children mentioned in our last edition. While we send out 'Don Bosco Today' without charging you will realise that we have to pay for the printing and postage. The cost of postage has recently increased. The Salesians, convinced of the value of the apostolate of the printed word, so dear to the heart of Don Bosco, are prepared to subsidise these costs considerably. However we would appreciate some help towards this considerable expense. We like to think that many people are helped and encouraged by the content of 'Don Bosco Today'. Your contributions to the expense of this magazine would be gratefully appreciated. Equally importantly, if you are tax payers, why not let the Government help the Salesians by completing a Gift Aid form? In a world of so much bad news, we would like to be able to tell more people about the good news, your help would make that possible.

Tony Bailey SDB

Editor

The Beginning of a Vocation

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. (Chinese Proverb) I left China in July 2000, waved off by dozens of my students who ran alongside the train as it left the small town, where I had worked as a teacher for two years. Everything within me wanted to stay. I loved it all, the work, the people, the culture. But I knew, that if I did stay, it wouldn't be part of any long-term plan for my life, I would only be drifting. Before I left, the Christian community I lived with asked me how they could pray for me. I asked them to pray for a full time job, teaching English, in a Catholic secondary school. They prayed with great enthusiasm, but I knew such a job was unlikely, as most schools are fully staffed before the summer holidays.

When I got home I moved in with my sister and her husband in Manchester. It was a difficult summer full of culture shock and uncertainty. There weren't many jobs on offer, and those that were weren't very enticing. One school advertised itself as sponsored by the Royal Bank of Scotland, making me long for my shabby classroom in communist China. Finally, in the last week of the Summer, I went yet again to buy the Times Educational Supplement. As he took my money the newsagent said, 'There's no point buying that at this time of year, hardly any jobs.' I agreed with him and trailed home only to find that there was a job. A school in Bolton, run by a religious order I'd never heard of called the Salesians, needed an English teacher, to begin immediately. The next few days were spent in a flurry of ironing, form filling, and researching about these Salesians. I was the only applicant. The interview was on Thursday. I began work the following Monday.

After two years of teaching the most polite people in the world, the average British teenager is a bit surprising. But I grew to love the school and its pupils very quickly. The Salesian way of life was a beautiful revelation to me, especially seeing it enacted in the everyday life of the school. Negative comments were not to be made to, or about, young people. Any suspensions or expulsions were genuinely regarded as regrettable. Christ was placed at the heart of the curriculum. I was constantly amazed at the faith of the pupils; at how many would voluntarily go to weekly Mass, and at how much money was raised for charity.

At the back of my mind all the time were questions, Why had God brought me home? Why had I felt so sure that it was time to come home? I was sure He had brought me home to show me what the future held. I was hoping that a handsome husband and children would be part of the plan. The young people at Thornleigh however had other ideas. They were constantly asking me if I were a nun, and wouldn't believe me when I denied it. They even spread the rumour among the staff. One day it occurred to me that perhaps they were right; perhaps I was called to the religious life. The idea seemed so dreadful, so against everything that I wanted to do, that I completely recoiled from it. I put it to the back of my mind, and tried to get on with life.

Getting on with life proved difficult. The thought of vocation wouldn't go away. It niggled at me all the time. I couldn't ignore it. I felt that I wasn't being honest with myself. One day I decided to screw up the courage to think about the idea properly. When I did, the idea of vocation didn't seem strange or foreign. It seemed completely normal, as though my whole life had been leading to this moment. Still the prospect of eternal chastity was fairly terrifying. So I prayed and asked God, that if this were truly my vocation, I could feel happy about it for at least a week. My prayer was answered. A week followed full of love for others, delight in my work and wonderful prayer times. At the end of the week I sat and pondered again, I still hadn't spoken of these thoughts to anyone but it was looking increasingly like I would have to. I baulked at this thought and so prayed again, this time asking for an unmistakably clear sign. I prayed, 'If I receive a sign, I promise that I will speak to a priest.'

That night I went to a healing Mass with a friend. It was to be a normal Mass, followed by a time of prayer for the sick. As the Mass ended the priest asked the sick to come forward for a special blessing. At first, only the very obviously ill went forward, but after a while everyone started to go. My friend and I, feeling a bit nervous, joined the line. I noticed that, when they got to the front, the priest would touch each person and bless them. When I reached him, he stopped and said in a loud voice, 'She has made a great promise.' I knew that I had received my sign.

I began my life with the Salesian Sisters when I entered their house in Liverpool on Friday 30th August 2002. I am now approaching the time of postulancy. Every time I reach a new stage in this journey, I feel exactly the same sense of fear and uncertainty as I did when leaving China three years ago. It is always daunting to make a commitment even when that commitment is only for a year. I am a long way from making even temporary vows, but I know that God has called me to be here now, for this time. He called me and planned this from the moment of my conception. The Chinese proverb states, A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. I believe that I've made several steps since I boarded the train at Yantai, that God has always been with me, and will continue to be so for all the hundreds of steps that lie ahead.

Katherine Taylor

The Missionary Vocation

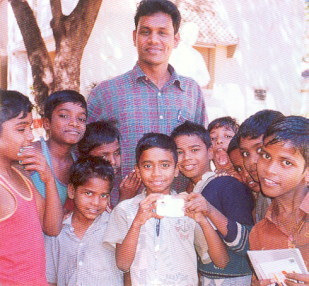

After many years looking after the Don Bosco Youth Club in Bootle and before taking up his new post as Chaplain to Salesian High School, Chertsey, Fr Pat Kenna recently spent some months working with our Salesians in South India. These are his reflections on the experience.

After many years looking after the Don Bosco Youth Club in Bootle and before taking up his new post as Chaplain to Salesian High School, Chertsey, Fr Pat Kenna recently spent some months working with our Salesians in South India. These are his reflections on the experience.Right from their very first years in India, unlike many other religious congregations, the Salesian missionaries started encouraging Indian vocations. Today there is a large and growing number of young Salesians dedicated to fulfilling the ideals and dreams of Don Bosco. When Fr Chávez, the Rector Major, visits India for their centenary celebrations in 2006, the Indian provinces are to make 25 young men available for the foreign missions. The Indian Government is marking the centenary by issuing a stamp.

The state of Tamil Nadu, in the southeast corner of southern India, encompasses two Salesian provinces, Chennai, formerly known as Madras, at the northern end, and Tiruchy in the south. Fr Theo, the Provincial of Tiruchy, has just reached the grand old age of 50. He is the twelfth oldest Salesian in the province, and there are almost 200 Salesians in his province. The average age of the whole province is somewhere around 30 years old. Tamil Nadu is a beautiful state and the Tamil people are wonderfully hospitable. Most live a poor village life in rural settings. It is in the small towns and villages where you will find most of the 22 Salesian communities, working among the poor. Even when they work in cities such as Tiruchy, Salem and Tuticorin they live and work in the poorest areas.

However, Tamil Nadu, even with its long established record of harmony and inter-religious tolerance and support, was the first state to enact the Anti-Conversion Bill in October 2002. This has the potential for making life very difficult for the minority religious groups of Muslims and Christians. These subtle, and not so subtle, political changes, in a country that prides itself on its democracy and secularism, are worrying. Even with all the darkening clouds on the horizon ordinary life continues and the lower caste Hindus (Dalits) are educated in Christian schools. This is seen as one way to tackle the incredible poverty and ignorance that exists in the villages of the region.

I was privileged to spend over three months as a guest of the province of Tiruchy. I saw so much, I felt so warmly welcomed and accepted, and I was treated so hospitably. I began my visit in The Retreat, the house of philosophy at Yercaud, a hill station in the mountains of central Tamil Nadu. To get there it took a long death-defying, almost perpendicular, stomach churning drive but it was worth it for the cool air, the spectacular views, the forest wildlife and of course, the hospitality of the Salesian community. I was so impressed by the young Salesians studying there. The everyday life for the young Salesian Brothers means regular prayer, commitment to study and to the night schools in the poorest mountain villages. All this with spontaneous laughter and fun, despite hard work on the estate and the house jobs, the involvement with the local schools, and the ruthless bare-footed games of football, basketball and volleyball. What was particularly impressive about most of them was their dynamic and dedicated desire to really change for the better the society in which they live, and their idealism, inspired by Don Bosco, to work with the poorest in the most difficult places. To this end, a number had even changed province and see themselves as missionaries within their own land, swapping the culture, language and tradition of Tamil Nadu and Kerala for the cities and plains of the north. A few have even elected to work in the northern region where three young Salesians were martyred only a couple of years ago.

After the cool mountain air of Yercaud, it was a bit of a shock to move to Salem. However, I had looked forward to being there for many reasons. I was tired of eating hot, pungent, vegetable curry and plain boiled rice, the staple food of Tamil Nadu. Also I was informed that Salem had a Pizza Hut and maybe a MacDonald's. Unfortunately the rumours turned out to be false. But honestly, the main reason I wanted to get to Salem was to experience the work that the Salesians and the excellent lay staff do in the city among the rag-pickers, hotel boys, bonded labourers, child factory workers, abandoned children, runaways and orphans. To say that I was impressed with the people and the whole place would be an understatement.

The project in Salem is on two sites, Adivarram and Anbu Illam. Adivarram is in the foothills of the mountains, 15 kilometres from the city centre, and about 3 km from the main road and bus route. This home houses about 60 of the younger children, the newly arrived, the children that attend the local village school, those who are not yet skilled enough to attend the city secondary schools, those that have just come off the street and a few who are pre-apprentices.

I decided to stay for a short time at Anbu Illam, house of love, in the city of Salem. This city has the rather dubious distinction of the highest female infanticide rate in the country, having the largest number of cinemas of any city, a growing street population, a huge bonded labour problem among young people and numerous other social issues. It is a noisy, dusty, overcrowded, dirty and smelly city; it is also extremely hot and sticky. The Salem District has had very little rain over the past couple of years, the monsoon rains have not reached this far into the country for a long time. The Salesian house is next door to a very poor Muslim slum.

Anbu Illam deals directly with many street children through outreach programmes, community social work, transit camps, child line and peripatetic workers. The house is in the heart of the old city and has a small community of three Salesians (two priests and one student), some lay staff and the older and more settled young people. Almost all the fifty resident youngsters, aged from 11 to 18, attend one of the local schools. During the day, the place is open to any of the young people who live on the streets. They come in to wash themselves or their clothes, find somewhere quiet and safe to sleep, meet a friendly Salesian face or just to chat and play.

Many of the young people who have lived on the streets for some time, find it extremely difficult to leave the street. In their minds the street affords them freedom from neglect and abusive adults. For them this outweighs the advantages they see in education and security. Therefore as much support and contact as possible is kept with them through the outreach programme. On the other hand many do desire to leave the poverty, dangers and grime of the street. They want a better opportunity in life. Those who do decide to come off the streets are interviewed and, if possible, they are returned to their families or villages. Those who have no one, do not know where they come from, or cannot be placed with suitable adults, are offered a place at Adivarram or Anbu Illam. Every boy in these homes has a story, some of them are heart-breaking and sad, some are harrowing, and many have the marks and scars to prove it. However, they are generally happy places, full of joy, laughter and hard work. It is a haven that gives them the opportunity to have hope in the future. They are places that breathe the very spirit of Don Bosco. I left my heart in Anbu Illam.

During my three months in India I learnt so much. I witnessed the fact that India is a land of wealth and real poverty, of noise and chaos, of tolerance and humanity. I was informed about corruption at the highest levels of society. I became proficient in eating with only the fingers of my right hand. I grew skilled in collecting water and washing in cold water from a bucket, I got used to having my hand held when someone spoke to me. I marvelled at the beauty of the land and the hospitality of the people, though I saw the de-humanising caste system in action. I encountered wild driving and wild animals on the roads. I also learnt about some of the difficulties that the Church in Tamil Nadu will have to face in the future. In fact I learnt so much, at all levels, that I am convinced that this wonderful country has a lot to teach all of us.

India is a land of contrasts and contradictions and I am grateful to the Salesians and the people for giving me this marvellous opportunity to experience so much.

Pat Kenna SDB

The Grandparents' Vocation

Alison buried her face in her grandad's cardigan and smelt the same aroma of soap and after-shave she remembered as a child. Now, aged 15, she felt comfortable that at least some things hadn't changed. But she also felt ashamed, that at her age, she still needed the reassurance of her grandad's presence through all that had happened. Her dad had just left home. He had never even said goodbye. Her Mum was angry, confused, saying things about Dad that left Alison upset and angry too. Her brother didn't seem to care. There was nowhere to go except to grandad. There, in his arms, she felt safe. She felt there that the family still existed. She discovered there some hope for the future.

Alison buried her face in her grandad's cardigan and smelt the same aroma of soap and after-shave she remembered as a child. Now, aged 15, she felt comfortable that at least some things hadn't changed. But she also felt ashamed, that at her age, she still needed the reassurance of her grandad's presence through all that had happened. Her dad had just left home. He had never even said goodbye. Her Mum was angry, confused, saying things about Dad that left Alison upset and angry too. Her brother didn't seem to care. There was nowhere to go except to grandad. There, in his arms, she felt safe. She felt there that the family still existed. She discovered there some hope for the future.Alison's story is not unusual. Grandparents are taking on an increasingly important role in caring for young people, and stabilising families in time of change. There are over 13 million grandparents in the UK at present. Each grandparent has an average of 4.4 grandchildren, fewer than in previous years. The monetary value of their care for grandchildren, in the UK alone, amounts to over £1 billion each year. This kind of care has increased in the past two generations, from 33% to 82% of children being cared for by grandparents. The increased divorce rates, the growing number of single parents, high house prices and the need for two incomes for each family, all suggest that the trend to increased involvement of grandparents will continue.

The good news is that grandparents have never been fitter, healthier, better educated and more mobile. Their life expectancy is higher than ever before in developed societies. The amount of time grandparents can offer to their children's families is a hidden treasure created by longer retirement and the ability to drive a car. In the past most grandparents lived within walking distance of their grandchildren. Today that is less likely to be true and distance can still be one of the most difficult barriers to grandparent support. One of the ways some grandparents are bridging the gap is with recent technology. The number of grandparents with mobile phones has increased, and the use of email means that young people can have direct access to grandparents even from the other side of the world.

Bridging the gap across the generations is one of the vital roles that grandparents offer. One writer has described the role as a gift between two people at opposite ends of the life journey. The real value of grandparents lies in their presence rather than their actions. Simply being there is enough. They become friends with their grandchildren, as advisors, storytellers and confidants. They can help to heal the inevitable tensions between parents and their children. Alan was in big trouble with his dad for lying about where he had been. He thought his dad didn't understand him until he talked to his Gran. "Oh, he understands you alright," she said. "He lied to me like that, and stayed away for a week at a friends when he said he was on a scout camp!" Alan laughed and grew in respect for his dad's nerve in getting a whole week away from home like that. Somehow it brought his dad closer to him.

Being a grandparent is no easy task. It is a vocation with very different demands from parenting. Grandparents are not usually the primary support for their grandchildren. They have to wait for their role to be offered to them. They have to bite their tongues many times as they see parents making different choices to their own. They have to watch mistakes being made, and be humble enough to help pick up the pieces. They have influence but little day-to-day authority. They feel deeply connected, but may not be consulted. They offer stability to others, but may not feel secure themselves. Grandparents live out a vocation that weaves the threads of family through generations, but that weaving is often in the background, beneath the surface of the busy life of young families. Cards, small gifts, phone calls, emails and visits are the threads with which they tie the extended family into a living reality.

The spiritual side of a grandparent's role can often be over-looked. As they look to the last third of their life journey grandparents have much to reflect upon. Success and failure, friendships, family and dreams all need to be sifted for the wisdom they contain. Questions about the purpose of life become deeper and more insistent. Looking back at the experience of life therefore puts them in touch with a longer view, a wiser outlook and a richness that can be offered to younger generations. The frustration of their role lies in having to wait for the right moment to share such wisdom and richness. That too is part of the spiritual challenge grandparents face, waiting patiently for those rare, almost magical moments, when they connect across the generations with their grandchildren. Those moments are spiritual experiences that can make the waiting worthwhile.

The relegation of grandparents to the family substitute bench, the acceptance of a support role, the need to wait for moments to share wisdom and support, all demand humility and acceptance from grandparents. Those qualities then weave back into their own spiritual journey, and join grandparents to a deeper human journey shared by all the family. The need for grandparents to reflect and to pray for their children and grandchildren is huge. Their ability to make sense of their own lives in terms of the Gospel, in terms of the cross and resurrection, is the best way to hand on faith to their grandchildren. Watching that gospel pattern emerge in their own family experience helps to give them wisdom, and the patience to wait for the right moment to share it.

In the early Salesian family story the grandparent role was taken by Don Bosco's mother Margaret. At the age of 68 she agreed to get involved with Don Bosco's children. In some ways she became a mother to the hundred or so boys eventually resident at the oratory. Margaret did many of the common sense things Don Bosco found difficult. She sat and spoke to the children at bedtime, helped them relax and told stories that eventually started the tradition of the Salesian 'goodnight' reflection. Margaret drew other women into relationship with the young boys and created a home. She told stories about her son that created a deeper connection between Don Bosco and the oratory boys. Whilst Don Bosco was rushing about in the city dealing with finances and plans for development, Margaret was constantly present, stabilising and maintaining relationships with a huge number of young people. It was Margaret that kept Don Bosco down to earth, slowed him down, kept his sermons simple and encouraged him to find more help. It was Margaret who welcomed visitors, cared for the sick and maintained a prayerful background role throughout the first ten years of the Salesian house in Turin.

As a model for grandparents, Margaret has some strong challenges to make in today's culture. She was able to accept a reversal in authority, and take direction from the child she had raised. Margaret had the courage to challenge her son, and make him think again, in a way few others would dare. She was content to do the practical and ordinary things out of a deep spiritual awareness that could occasionally be shared with the young people in the house.

The same pattern of wisdom, practical help, patience and spiritual depth are still needed today from the 13 million grandparents in the UK. Children, growing into our increasingly fractured society, need these rocks of common sense, humour and spiritual depth more than ever. In our Salesian family such older members have a respected role, living out a gospel faith with patience, courage and wisdom on behalf of the young. Children like Alison, in her grandad's embrace, will be forever richer, wiser and healthier because of their goodness. God bless all grandparents.

David O'Malley SDB

Reflection

Like a child, with anxious eyes,

We are nervous of the road.

God, as a calm mother, guides

Our vocation, safely home.

The Vocation of Witness

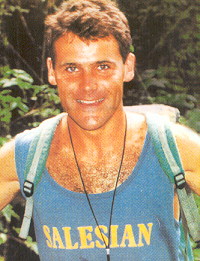

I first met Sean Devereux in May 1982. I was working in Liberia and during a short holiday I visited Salesian College, Farnborough, to talk to the sixth form. I must have spoken well, because at the end of my talk, Sean, who was the School Captain, said he was planning a gap year before University, and he would like to join me in Liberia. My advice was that he should get some qualification and experience first. After studying at Birmingham and Exeter Universities, and teaching at our Salesian School in Chertsey, he volunteered again in 1988. Once he was accepted, he asked if he could possibly go up to the interior mission in Tappita, where he thought there was more need.

I first met Sean Devereux in May 1982. I was working in Liberia and during a short holiday I visited Salesian College, Farnborough, to talk to the sixth form. I must have spoken well, because at the end of my talk, Sean, who was the School Captain, said he was planning a gap year before University, and he would like to join me in Liberia. My advice was that he should get some qualification and experience first. After studying at Birmingham and Exeter Universities, and teaching at our Salesian School in Chertsey, he volunteered again in 1988. Once he was accepted, he asked if he could possibly go up to the interior mission in Tappita, where he thought there was more need. I remember him as being the life and soul of the party, joining in the fun and games, especially where children were involved. His energy was boundless. "He had a great love of children and was in the forefront of organizing games for those he was helping," remarked Tim Jones, correspondent for 'The Times' newspaper. He liked to dress up in top hat and tails and do a crazy conjuring trick, much to the delight of the African children, who gathered around like moths to a flame. Mike Emery, his no-nonsense Australian friend who he met in Monrovia in 1990, recalls how a four-year-old and six-year-old used to walk for miles and cross six check-points just to hang out with him, then trek back home again at the end of the day. As Mark Thomas, UNICEF spokesman said, "The children loved him very much, he was a real friend in Somalia."

Who, but Sean, would have thought of converting a fleet of United Nations food trucks into mobile Christmas grottos? In his own words, "With my workmates, we were clad in our silly Father Christmas uniforms, whirling around the city, bringing presents and food to the various hospitals and orphanages. One has to keep sane!" One time he was thrown in jail by one of the warlords. He was trying to obtain the release of a child soldier. He loved to tell how the jailer asked him why he had been put there. Sean replied, "I don't know." But the jailer insisted, "I've got to put something down, otherwise they will shoot me." So Sean said, "Just put pending." He overheard another soldier ask the jailer what the newcomer was in jail for, to which the jailer replied, "Oh, it must be something very serious. He's been pending." The boy was eventually released through Sean's persistence, but only after two more weeks.

Compassion was something second nature to Sean. Not only could he not bear seeing people suffer, but if there was a way of helping anyone, he would try whatever was possible. He liked to see smiles on people's faces. I remember, as he was about to leave Liberia, he wanted to fulfil one duty he had been unable to carry out earlier. There were three places where he had buried the remains of some of the innocent people killed in the civil war. He was upset that the families of these people had not been able to be there to pay respect to their relatives, who had needlessly died. He enlisted the help of his friend Mike Emery, and a group of young boys who had been child-soldiers; they put up notices, and asked me to pray that these tragedies to civilians would never happen again.

Courage was something that seemed to come naturally to Sean. This, it was obvious, had been instilled in him from his earliest years. "If there's something wrong," his father had said, "you must have the courage to say so." He was in tears on one occasion, finding out that some of his former pupils had been killed in the Liberian war, voicing his outrage with the words, "To use children as warriors, that's really evil." It is estimated that during the Liberian civil war 15,000 children were warriors.

While in Somalia, he organized a football tournament which attracted 2000 fighters who lay down their arms for its duration. He publicly condemned the warlords in Somalia, but he was not blind to those who had armed them, condemning the production and delivery of weapons to that country. I wonder what Sean would be saying if he were alive today, when UK arms sales to Africa have risen fourfold since 1999, an estimated £200m for this year. Moreover the UK gives £760 million of export subsidies to the arms trade, which would provide 100 schools or 10 hospitals in this country, let alone Africa.

It takes courage to stand up to anyone cheating or taking unfair advantage over others. He was expelled from one county in Guinea, where he was a Food Monitor with Liberian refugees. In his own words, "Human beings have an enormous capacity for evil. I caught the chief of customs stealing refugee rice and decided to ask why." This was in reference to what he had witnessed when 6500 refugees from Liberia arrived in Guinea. They had travelled for nine days and were made to wait for a further four days without food and water. He saw soldiers and police on top of containers passing tap water in 10 litre bottles in exchange for US $10. "Their desperation was deliberately exploited to the full," he commented. "I hate it, I suppress my anger, then I do everything legally possible to change it, and I find ways of beating the system."

Service to others is embodied in his now well-known motto,

"While my heart beats, I have to do what I think I can do, and that is to help those who are less fortunate."The editorial in 'The Inquirer' newspaper in Liberia, a couple of days after Sean Devereux was killed in Somalia in 1993, had this to say,

"Africa, it seems, has a way of biting the hand that feeds it. Sean Devereux had to fight his way through rebel checkpoints to get relief food to the people of Zwedru; he endeared himself to the youth of Monrovia when he organized the 'Peace and Unity Race' for about 10,000 people in early 1992. He was the organizer of the Special Emergency Life Food programme for 750,000 people in Monrovia. So we can see that he was not a behind-the-desk relief worker. He served humanity by putting life into whatever he did. He accomplished his aims by building monuments into the hearts of those he served. Some day a monument will be built to all those who struggled to revive sanity in our society, and the names of the five Nuns who were killed and Sean Devereux will top the list."

How appropriate the words of the former UN Secretary General, Dr Boutrus-Boutrus-Ghali,

"In adverse and often dangerous circumstances, Sean showed complete dedication to his work. His colleagues admired his energy, his courage and his compassion. Sean was an exemplary staff member and gave his life serving others, in the true spirit of the United Nations. Sean was a real soldier of peace."

What a vocation!

Joe Brown SDB

Mission Director

The Vocation of Teaching

As a fifteen year-old pupil I was taken on a school visit to a Vocations Exhibition being held in Glasgow. At the end of the afternoon I was late back to the meeting place. My teacher said, I presume in humour, "Well, Helen, have you chosen your Order?" My reply was, "Yes, Miss!" I had immediately been attracted by the brightness of the display and the warmth of the Salesian Sisters. Although I had never met them or heard of them before, I wanted to join them, and work with young people. I like to think this was inspiration.

As a fifteen year-old pupil I was taken on a school visit to a Vocations Exhibition being held in Glasgow. At the end of the afternoon I was late back to the meeting place. My teacher said, I presume in humour, "Well, Helen, have you chosen your Order?" My reply was, "Yes, Miss!" I had immediately been attracted by the brightness of the display and the warmth of the Salesian Sisters. Although I had never met them or heard of them before, I wanted to join them, and work with young people. I like to think this was inspiration.My first job in Liverpool was in 1966 as Laboratory Technician in Mary Help of Christians High School. I was already a Salesian Sister, and this was considered to be a good way to start before going to College. I loved my year with the students and really appreciated the opportunity to experience full-time apostolate. In 1971 I returned as a fully-fledged teacher, and have remained here for my whole teaching career. In those early years I enjoyed my contact with the girls, as a teacher of Mathematics, a form tutor, in the classroom, on the playground, and on residential trips and holidays. I was extremely happy in all that I did.

In time, I took on more responsibilities. I found these challenging, stimulating and enjoyable. In 1980 I was appointed Deputy Headteacher. Two years later I found myself being interviewed for the post of Headteacher. I accepted the responsibility with great fear and trepidation. Four terms later the Catholic schools in Liverpool underwent reorganisation, forty-two schools became fifteen. Our new school, as the result of amalgamation, became the Comprehensive school we have today, St John Bosco High School.

Looking back over nearly 22 years as Headteacher I wonder at the changes that have taken place. Many for the better I am pleased to say. There were periods of great stress as well, for example, during the militant period in Liverpool when the City Council ran out of money and handed notices to all its employees. When I look around the wonderful buildings and gardens we now have in our school, and in the Bosco City Learning Centre, I am reminded of the buildings we used to have. The original Mary Help of Christians building almost fell down before it was finally demolished. We had to fight to get the excellent buildings we have today. I saw this as fighting for children's rights to the best education.

As a young teacher my dream for every student was that they use their talents to the full, have the opportunity to become the best possible person they can, and be prepared for their future adult lives. My dream has not changed, but my way of achieving it has. As a young teacher I lived out that dream in the classroom, in the playground, what we used to call at the chalk face. As a headteacher I still wanted to be seen in the playground, even though not so energetically! However I know that my dream can never be realised by me, it has to be a dream to share, a dream to encourage others to dream. As headteacher I was blessed with staff who shared that dream. My privilege was to encourage them, give them the opportunity to make the dream happen for the students in this school. And they did, in ways I could never have believed possible. One of the great consolations of Salesian headship is to see the way that staff, given encouragement, can achieve what I could never achieve. Visitors so often remark about the family atmosphere they feel when they come into the school. The spirit of a school is distilled from years of kindness shown, until it becomes a way of life. Being kind to fractious volatile teenagers is no easy task, and can only be done consistently if all staff buy into the process. While demanding standards of courtesy from our students we make great demands on ourselves. Mutual respect can never be imposed.

I have tried to keep my eye firmly fixed on the ideals of a Salesian School, despite the tide of Government red tape and bureaucracy that threatens to drown us in paper. Government edicts cannot be ignored. I suppose the great challenge that we all face in schools is to ensure that we don't lose our dream when pressurised by change. While the demands of government initiatives of recent years makes the job a very different one from that which I undertook all those years ago, I have had to make sure it never changed my dream. The good of the students has to remain our primary criterion in every decision. So many things change, we have introduced the National Curriculum, Key Stages 1-4, SATs examinations, not to mention the GCSE. We have been under the microscope of OFSTED inspections. Schools are facing even greater changes in the coming months. However, some things must never change, our commitment to the good of our students.

The problems have been more than compensated for by the wonderful and exciting times that I have experienced. I love all the students, even the most challenging. We have constantly reminded ourselves of Don Bosco's advice not only to love the children but to let them know we love them. The young people of Liverpool are so talented and have a tremendous sense of humour and fun. They are generous, as they have shown so often. Many of our former students look back on their school days with great fondness and gratitude, and since the announcement of my retirement I have received several letters telling me this.

My retirement from the post of headteacher has reminded me that the number of Sisters has decreased, and so for the first time in the history of the school we are handing the school over to the care of a lay headteacher. I know that parents and staff are anxious that the very distinctive Salesian ethos, which is so evident in our school, continues, is nurtured and goes from strength to strength. It will. Why? Because what we have achieved, we have achieved with the staff we have, and they remain. The greatest consolation I have, as I leave this school, is to know that the dream, which has driven me, drives them. The school, with its new leadership, is in safe Salesian hands. Support and encouragement will always be there from the Salesian Sisters and from the Salesian governing body. The school remains safe in Salesian hands, I am sure that it will go from strength to strength in the years to come.

Helen Murphy FMA

A Vocation Explained

Vocation is no abstract thing, it is about people like you and me. Let me tell you the story of my own vocation. I come from a rather large family. I've five brothers and six sisters. Although practising Catholics, nobody in my family became a priest or a Sister. As a child it had never crossed my mind that I might be a priest. So, what happened that made me change my mind?

Something very simple! I was eleven years old, a pupil in the Salesian school at Saltillo, in Northern Mexico. Quite suddenly my mother became ill, and two weeks later she died. Three days before she died, I sat by her bedside talking to her. Unaware of how ill she was, I was more concerned about persuading her to buy me a pair of trainers. I was really keen on playing basketball at school, and desperately needed a new pair of trainers. I was hoping she would give me the money for them. Her mind was elsewhere, "I've always prayed that one of my sons would be a priest, I have six sons, and so far not one has entered the seminary." I spotted my opportunity, eager to get my pair of trainers, I said to her, "I'm the one you've been praying for." She smiled in contentment and gave me the money for my trainers. She died three days later. What is fascinating is that I went for a pair trainers and I ended up with a vocation.

A few days later I went to my teacher, and simply told him that I wanted to become a Salesian priest. Of course, I didn't mention my mother's prayers. I never referred to the incident until fourteen years later, on the day of my ordination, when I said to my father and my brothers and sisters, "Perhaps you would like to know why I became a priest." And I told them about the trainers.

To have a vocation means to discover that life has a meaning. A vocation gives life a direction, a powerful energy to reach out to new horizons. It means we are fully motivated; we have a reason for being who we are, and doing what we do with joy, optimism, and the conviction that we are of value. Consequently, I believe that the most common crisis among young people today is not their addiction to drugs or to alcohol, or their confusion in the area of sexuality, but rather, the lack of meaning, direction, and motivation in their lives. They feel tempted to enjoy to the full only the present moment, to experience moments of strong emotions, or to give in to a life of indifference.

One lesson I have learnt with regard to vocation is that we need to invite and challenge young people. It's a lesson I learned from personal experience. Early on in my Salesian life, when I was teaching, there was a boy in my basketball team who eventually joined the Christian Brothers. Later while I was studying Theology, he wrote to tell me that he had decided to join the Brothers, and that, up to a certain point, he had been disappointed because I had never challenged him to become a Salesian. I was glad he was honest with me, he taught me an important lesson, that when it comes to vocation young people need to be challenged.

An opportunity came my way in Tijuana, a city along the boundary between Mexico and the United States. Groups of Mexican, American, Canadian, Italian, Spanish, and German volunteers work together with the Salesians. We have almost always had wonderful young people, of superb human calibre, truly Christian and Salesian. Among them there was one, from California, who had come from a Jesuit university. He seemed so very much at home with us. He was a genuine Salesian, generous, with a great capacity for working among poor boys, especially those at risk. Sometimes he even landed in jail, because the police saw him with boys who were on drugs and they thought that he was a drug dealer. He was about to complete two years as a volunteer. During a visit to Tijuana, I found him in bed, with influenza, and I put it to him straight, "Steve, have you ever thought of becoming a Salesian?" And he answered, "No, no one has invited me." So I said to him, "Hey, you have so many good qualities, and I would be happy to see you a Salesian one day." And he answered, "Maybe I have to give God a chance." Today, Steve Gomez is a Salesian priest. He does great work in a youth centre in Los Angeles East.

On the other hand, another young volunteer, also American, told me, "I've discovered my vocation, working for young people. I will always work for them, as Don Bosco did, but I feel that my vocation is for marriage." Today, he is married, and together with his wife, he works in youth ministry in one of the dioceses in the United States.

I think that in the West, there are several factors which decisively run counter to the consecrated life:

- The drop in population, if there are no children for society, there are none for the Church.

- Secularism which does not recognise a religious challenge.

- The high standard of living, the comfortable life, which has no place for self-denial, sacrifice, and definitive commitment.

- So often the State is capable of running works which used to be in the hands of religious (schools, hospitals).

In contrast, in the developing world there are elements which favour consecrated life:

- The population is predominantly young.

- The cultural base is still strongly religious.

- Poverty is so widespread that people feel the need to do something to assist others, especially since the State does not have the resources to address these needs.

Most of our Salesian vocations now come from India, Vietnam, East Timor, and some countries of Latin America, Poland and the Ukraine.

One country we must mention is Vietnam, the province that is growing relatively more rapidly than any other. We are talking about a communist country, under a totalitarian regime, where Buddhism is the predominant religion. Here we have four hundred young men preparing for the Salesian life, all of them university students.

It seems therefore that the consecrated life is more suited to poorer countries. But this does not mean that the Salesian vocation is not for the rich countries. In fact Salesians are present in almost all the Western countries. It simply means that in developed countries, the consecrated life has another function: to be a visible, credible, and legible sign of God for an atheistic society, which lives as if God does not exist. This can be done to the extent that consecrated life truly confronts the existing culture, with an identity based on the Gospel, strongly centred on God, bearing witness to community, and evident in total dedication to others.

By way of bringing this wonderful day to an end, I should like to leave a final message for the Salesian Family in Great Britain. You know that time, and therefore also the future, is a grace and a challenge. It is a grace that the Lord offers us, so that we may carry forward his marvellous loving plan for mankind. It is a challenge because He counts on each one of us, as He counted on Mary, on Don Bosco, on Mother Mazzarello, on so many men and women throughout history, who knew how to actively collaborate in the building of the Kingdom, to make this world more human.

The message consists in three watchwords, that should become the programme of life and action for the whole Salesian Family.

- The first word is to grow. We have to grow in number, in our Salesian identity and in the depth of our spiritual life. To grow not only because there is strength in numbers, but because Don Bosco had all the youngsters of the world in his thoughts. There are so many who have no one close to them, no one taking an interest in them, helping them as they are growing up, looking for their place in life. To grow in quality, Jesus wants us to be salt, to be light, to be the leaven. Therefore Grow!

- The second word is to be united. In the Church and in the Salesian Family, it can happen that there are many groups without any links between them, so that they are more like a field of mushrooms, without a common trunk, without branches and therefore without fruit. We need to know one another, love one another, and help to form one another together.

- Finally the third word is to create synergy, working together to produce an effect which is greater than the sum of our individual efforts. Don Bosco said that a single thread is very weak and easily breaks, but if we weave it together with another, and then another, it becomes a strong cord which is very difficult to break. So with us, alone we can do little, but if we work together, we become more effective. This means planning together, and while respecting each others' autonomy, taking decisions together about working with young people, about vocation promotion, about the Salesian Bulletin, about volunteers.

This is your opportunity! This is the grace being offered to you!

Pascual Chávez SDB

Rector Major

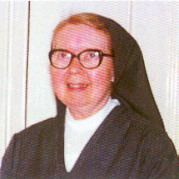

Sister Mary Twigg FMA 1914 - 2003

On the evening of Saturday 22nd March, in the John Radcliffe hospital in Oxford, Our Lord called to himself our sister, Sister Mary Twigg. She was born in Macclesfield on the 25th September 1914, professed in Cowley, Oxford on the 5th August 1939.

On the evening of Saturday 22nd March, in the John Radcliffe hospital in Oxford, Our Lord called to himself our sister, Sister Mary Twigg. She was born in Macclesfield on the 25th September 1914, professed in Cowley, Oxford on the 5th August 1939.Mary was the third child in a family of four. Her mother died when Mary was just eleven years old. In the same year she won a scholarship to the High School. When she matriculated six year later she worked as a student teacher. Her family home was only three miles away from Shrigley, the missionary college opened by the Salesians. This was how she got to know the Salesians. She entered as an aspirant in Chertsey in 1936, and went to Cowley for her novitiate the following year.

During the Second World War, Mary continued to teach and work in the youth club in Chertsey and then in Farnborough. She then went to college in Southampton where she qualified as a teacher, gaining a distinction in Advanced Religious Knowledge. She taught children in primary school, mostly in Battersea, until her retirement in 1978.

In her retirement years, Mary continued her apostolate. She went to Hastings where the community had a house near the sea. She began to work for London school children, helping teachers to bring groups for three-day retreats. She also helped in the provincial office for three years. After a second cataract operation, it was decided that close secretarial work was not good for her sight. She stayed in the community at Hastings until it closed and then returned to Battersea where she worked as cook for the community. She was able to take Holy Communion to residents in three nursing homes in the area.

She seemed to recover well from a stroke, but it had affected her speech, and gradually, over a period of years she lost the ability to speak. She never lost her deep serenity which showed through in her sudden warm smile as she recognised anyone who came to see her.

She was particularly proud to belong to an English family that kept the faith throughout the Penal Days, and she found that faith again in what is dear to our Salesian Family, love of the Mass and Our Lady, and loyalty to the Holy Father. Thank you Mary for the love and dedication you brought to us in this province, may you now rest in peace.

Elizabeth Purcell FMA

Provincial