I wish to thank the Salesians of the GBR Province on behalf of all the population of South - East Asia for the generous donation of 35,822 Euros that you gave for the Tsunami Emergency. We want to express our gratitude because, with your contribution, you gave hope to numerous orphan youngsters who have been affected by this tragedy and supported by the Salesian community present in the region.

We are constructing day centres for poor and orphan children, giving economic support to the families most hit by the tidal waves, providing student grants, constructing small brick houses, purchasing boats, nets and further equipment, with the participation of the population and above all with the collaboration of the local Salesian communities.

Thanking you again for having promptly thought about the people in need, we wish that your support may continue in the future and may bring further help, in particular to the hundreds of children and youngsters that in this tragedy have lost their families and closest relatives.

Don Ferdinando Colombo SDB Volontariato Internazionale per lo Sviluppo

|

Title: Shelter and First Emergency Aid for Displaced People in Negombo - Sri Lanka Total cost of project: Euro 100,000 Your contribution: Euro 35,822 Objective: Establishment of temporary shelters for the displaced and catering for emergency needs including water and food security and medical care. Activities:

|

Fr Anthony Bailey SDB

In 1993 I went, with a few Salesian friends, to Greenbelt, the Christian Arts festival that runs over the August Bank Holiday. That weekend, I heard an amazingly catchy song called Bannerman by an artist called Steve Taylor. It was a tribute to the people who went to football matches, athletics events and the like and, when the camera came onto them, held up a banner that said, simply, John 3:16. I was reminded of the song and the banner as I walked around the grounds of Westminster Abbey on the night of Friday 15th April this year. Like many thousands of others, I had made my way to London for the Make Poverty History Vigil, and had found that there were too many of us to get into the Abbey, for the star-studded opening service.

In 1993 I went, with a few Salesian friends, to Greenbelt, the Christian Arts festival that runs over the August Bank Holiday. That weekend, I heard an amazingly catchy song called Bannerman by an artist called Steve Taylor. It was a tribute to the people who went to football matches, athletics events and the like and, when the camera came onto them, held up a banner that said, simply, John 3:16. I was reminded of the song and the banner as I walked around the grounds of Westminster Abbey on the night of Friday 15th April this year. Like many thousands of others, I had made my way to London for the Make Poverty History Vigil, and had found that there were too many of us to get into the Abbey, for the star-studded opening service.Fr Martin Poulsom SDB

The Chinese have a saying: May you live in interesting times. This seems true of our era. Change has become the common feature of our culture. An old world is collapsing around us while a new one is yet to emerge. This affects every aspect of behaviour. Our culture is restless, distracted by the trivial and characterised by a loss of meaning and a deep cynicism. There are no heroes now. All have feet of clay. It may explain why politics seems to have lost its optimism and is dominated by phrases such as the war on terror, the clash of civilisations or the end of history. In this time of numbness, religion appears, on the one hand to be in numerical decline, while on the other it is increasing in fundamentalism and simple certitudes: simplistic answers for a complex world.

The Chinese have a saying: May you live in interesting times. This seems true of our era. Change has become the common feature of our culture. An old world is collapsing around us while a new one is yet to emerge. This affects every aspect of behaviour. Our culture is restless, distracted by the trivial and characterised by a loss of meaning and a deep cynicism. There are no heroes now. All have feet of clay. It may explain why politics seems to have lost its optimism and is dominated by phrases such as the war on terror, the clash of civilisations or the end of history. In this time of numbness, religion appears, on the one hand to be in numerical decline, while on the other it is increasing in fundamentalism and simple certitudes: simplistic answers for a complex world.Fr Michael Cunningham SDB

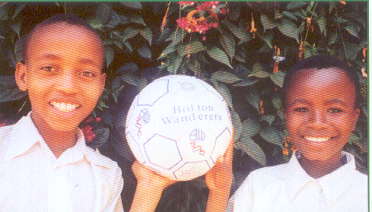

Contrasts sharpen our perception. I am presently engaged in the training of young African Salesians in Tanzania. Our house lies in the peaceful surroundings of the village of Shirimatunda, on the lower slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. In the evenings our playing field is opened to the local youth and at weekends our students run activities for them. Just across the hedge from my room is a play area from which I hear the happy sound of lively children. Many play in bare feet, using their own kiboli, a football made from plastic bags, ingeniously packed into a string net. Ki means little and boli derives from the English, ball.

Contrasts sharpen our perception. I am presently engaged in the training of young African Salesians in Tanzania. Our house lies in the peaceful surroundings of the village of Shirimatunda, on the lower slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. In the evenings our playing field is opened to the local youth and at weekends our students run activities for them. Just across the hedge from my room is a play area from which I hear the happy sound of lively children. Many play in bare feet, using their own kiboli, a football made from plastic bags, ingeniously packed into a string net. Ki means little and boli derives from the English, ball. Fr Brian Jerstice SDB

There is one thing more. The mystery at the heart of young people, whether you call it God or not, is the key to building the respect that is at the heart of the present Government agenda. The sacredness of each life, made in God's image, is the reason for respect; it holds the motivation to give and receive respect from one another. It is a sacred life that we all share. It is the reason we fall in love, why we grieve and make sacrifices and the basis for every community and family. Don Bosco would want us to remember that, even under a hood, we belong to God, meet God in each person, and are on a shared journey to deeper life in God. Perhaps the wildness of youth today is symptomatic of a society that has forgotten how close God is.

There is one thing more. The mystery at the heart of young people, whether you call it God or not, is the key to building the respect that is at the heart of the present Government agenda. The sacredness of each life, made in God's image, is the reason for respect; it holds the motivation to give and receive respect from one another. It is a sacred life that we all share. It is the reason we fall in love, why we grieve and make sacrifices and the basis for every community and family. Don Bosco would want us to remember that, even under a hood, we belong to God, meet God in each person, and are on a shared journey to deeper life in God. Perhaps the wildness of youth today is symptomatic of a society that has forgotten how close God is.Fr David O'Malley SDB

Fr Pascual Chavez Villanueva SDB (Rector Major)

Fr Ainsworth was born on the 5th May 1908, in Bolton. He came from a strong Catholic family tradition. Before the First World War the family went to America, in search of a new life, his mother died there and the family returned in 1913 on the Mauretania.

Fr Ainsworth was born on the 5th May 1908, in Bolton. He came from a strong Catholic family tradition. Before the First World War the family went to America, in search of a new life, his mother died there and the family returned in 1913 on the Mauretania.This is just to say thank you so much for your encouraging and positive words, and also for the wisdom and bedrock humanity you brought with you to Lysterfield when I was there in 1967 and 1968. These are precious qualities in any age, no matter how enlightened it considers itself to be, and in any form of living the religious life, perhaps the most important lesson anyone has ever taught me.

I have a fair knowledge of the history of the province, and on that scene, I see you as a significant and happy and healthy influence for more than half of the province’s lifetime. I’m glad I knew you, I have always been touched by your kindness, and I am proud to have benefited from your friendship.

Proud to know you? Very many, untold numbers of people, men and women without number?

Stolen from Fr Francis Gaffney SDB by its present owner W A Ainsworth. Restitution will be made.

Fr Anthony Bailey SDB